|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tell me the story about how the Jews and the Israelites ended up being defeated and enslaved by the Babylonians.

After Nebuchadnezzar defeated the Israelite armies and Jerusalem was

destroyed, quite a large proportion of the Israelite people were

deported to Babylon itself. And the estimates vary significantly. Some

say as few as ten percent. Some of the numbers that we get from the

ancient history say almost all the people were taken away. No matter how

many were actually taken, it is a significant experience that the people

had to go away and live in a foreign land. And we have quite a number of

poignant scenes from the Hebrew scriptures which reflect the trauma of

this event of being separated from Jerusalem, and how we will worship

our lord in a foreign land.

And then when the Jewish people found themselves subject to this all-powerful Babylon and these great images of power did this lead to a sort of agonizing reappraisal about what their own God was worth or meant or how powerful he must be? The destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar had a profound effect

on Jewish thinking and theology. For one thing, the promises that had

been given to David now had to be questioned. What did God mean by

saying the throne of David would last forever, when obviously it had

just been toppled? So the Babylonian exile is really an important

watershed in the development of Jewish theology as they began to think,

what went wrong? Has God abandoned us? Is [the Babylonian god] more

powerful than our God? Or is there some other reason why this fate has

befallen us? Maybe it's not God's fault. Maybe it's our fault. Maybe

it's our sins that have caused this. And in the process of this thinking

they start to take the trauma of the destruction of Jerusalem and the

Temple and turn it inward as theological reflection. There's a profound

effect on all later Jewish and Christian theology. So if we think about the political struggle that has just taken place with the defeat of the Israelites' Jerusalem, the city of God has been conquered by Babylon, the city of the enemy of God's people. Jerusalem and Babylon then forever thereafter will stand as the symbols of this opposition. The forces locked in a battle of good and evil for all eternity. ... If we imagine the experience of the exiles living in Babylon, the idea of Babylon itself comes to symbolize enslavement. Oppression. The notion of exile or alienation. In contrast to Jerusalem which is home. So these two symbols, really--Jerusalem home; Babylon exile, enslavement, oppression--will always be at the center of a lot of the trauma of apocalyptic experience. And the hope that it also provides for that idea of release, triumph and going home. ... As a result of the defeat by the Babylonians, Jewish tradition both during and after the exile really has to rethink its history. And this rethinking of history of the story of the people from times past is carried out by actually writing or in some cases rewriting parts of the biblical text itself. And so in fact much of what we think of as the Hebrew scriptures or the Old Testament as it is called by Christians is really a product of the re-thinking that occurs after the Babylonian exile. ... The process of re-writing the scriptures is somewhat easy to

understand if you think about it. Here is a story that starts with God

choosing Abraham and leading the people out of exodus and into a land of

promise, and selecting a king, David. But after the fall of Jerusalem

that story now obviously continues. At the same time though that they

continue writing the history they go back and reflect on how the earlier

story must be understood. So whereas earlier it's a story of God's

promise to Abraham and David, after the exile the new theology tends to

emphasize, well, that promise is conditional. If we don't live up to our

end of the bargain, if we don't remain faithful to God, God will allow

us to be punished. And this new way of thinking about the theology--what

we call the covenant theology--is an important new dimension of Jewish

thinking. And it's filtered through all of the biblical books that are

put together in this period after the exile. ...

The Babylonian empire that conquered the nation of Israel ... despite its opulence, nonetheless had a rather a short reign thereafter. Within approximately fifty years after the destruction of Jerusalem, the Babylonian empire, itself, had been overthrown by the Persians who had moved into the Mesopotamian region from farther east beyond the Persian Gulf. The Persians overran the city. It's quite an amazing story ... As the story goes, they actually dam up the canals that feed the city and come in through the water channels, invade the city secretly, throw the gates open and a massacre ensues. So this great city of Babylon, the city that conquers everyone else ... all of a sudden is conquered itself. And this reversal, this rapid change, comes to be viewed in a new way even by the Jewish people. God got his revenge at last. ... For example, in Isaiah, chapters 44 and 45--a portion of the book of Isaiah actually written during the exile itself--we hear of Cyrus the great Persian king referred to as God's anointed one. The Lord's Messiah. And it even goes on to say he will be a shepherd for my people. Now this is God speaking. He, Cyrus, will be a shepherd for my people and he will be the one to rebuild Jerusalem. ... So here's what this text from Isaiah is beginning to show us. A new

way of thinking. Now instead of just feeling traumatized over the

destruction of Jerusalem, now one can look back and say, "Oh, maybe

there was a plan of God all along. Yes, our God, in the final analysis,

is in charge of all human history. Look, he even directs foreign kings

to do his will for our benefit." ... So following the age of Babylonian control in the Middle East, the

Persian is really the next great empire. Interestingly enough, part of

the story of the Jewish people throughout this ancient period is that,

after the Babylonians, the Jews will almost always be under the thumb of

one or another of the world's great powers of the ancient history. And

that's going to create new influences ... [The Persians], in fact, are a

source for a major new component. One of the important features of

Persian religion, the religion that we usually refer to as the

Zoroastrianism, named after the great prophet of this tradition,

Zoroaster--or sometimes called Zarathustra. Zoroastrianism has a much

more dualistic way of looking at the world. In the Persian mythological

tradition we have Ahriman, the evil god who is at war with Ahura Mazda,

the good god, the god of light. ... Good versus evil. Now, on the one

hand this has some similarity to the combat myth that we hear of in

other ancient near eastern societies. Only now it's the good and evil

themselves thought of as abstract entities that dominate the world. That

gives a new dimension. ...

... After a century of war between Greece and Persia, finally, Alexander [sweeps] through the Middle East, defeats the last of the Persian kings, Darius III. And instead of stopping, [Alexander the Great] continues to conquer much of the rest of the Middle Eastern world all the way over to the Indes River Valley. Egypt, Syria, Palestine, all fall under Alexander's power. ... One of Alexander's self-conscious policies is, as far as we can see, to bring Hellenistic culture to these conquered peoples. There's a great deal of emphasis on imparting Greek ideals and Greek culture throughout this new empire of Alexander. ... One good example of the emergence of Greek influences in Jewish tradition, after the conquest of Alexander the Great, is the document that we know as First Enoch. Now First Enoch was written somewhere between around 250 BCE and 200 BCE, in the early phase of Greek control of the Middle East. And First Enoch reflects the tensions that face Jewish tradition as a result of these Greek influences. On the one hand, First Enoch is extremely, intensively Jewish. It is a retelling of the biblical creation story and the early chapters of Genesis with an idea of our God being in control. So in that sense, it's very traditional. On the other hand, the way it tells that story of Genesis clearly has elements of Greek influence within it. ... It's the story of Enoch, one of those characters before the flood. Genesis Chapter 5. And in this story Enoch is taken away to heaven. ... Now what he sees then is something that the biblical story doesn't describe. He sees the rebellion of the angels. This too is based on Genesis, from the story in Genesis 6 where the sons of God rape daughters of men and produce a race of giants. Only now in First Enoch this is the rebellion of the angels under their leader, Azazel, whom we'll later call Satan... . So First Enoch gives us some of the most important components of what

we think of as later Jewish and Christian apocalyptic tradition. We have

God and Satan, good and evil. We have angels. The story of Genesis about

the sons of God now have become the angels. In fact in the book of First

Enoch, these angels are also called the watchers. They're the stars in

heaven. At least the ones who don't fall. The others are the demons of

hell. And importantly we have a cosmic battle thought of in these very

dualistic terms where the forces of God and the forces of Satan will

fight for control of the universe. But the stage for this battle, the

battleground itself, is earth.

The Jewish experience under Greek rule initially seems not to have had a kind of political resistance. There's a strong emphasis on retaining Jewish religion and identity, but they're not talking about the Greeks as oppressors, and certainly not as an evil empire. That perspective will change radically about the beginning of the second century BCE, around the year 200 when the Ptolamaic Greeks, that is the Greeks from Egypt, who had previously been in control of Jerusalem and Judaea, gave way to the Seleucid Greeks in Syria. And under Seleucid rule the experience of Jerusalem and Judaea will be quite different. In part because the program of Hellenization of the Seleucid Greeks is much more oppressive, and it's much less tolerant of Jewish religion and identity and that's where we're [going to] get some really important new tensions that are [going to] shape the political experience of the Jews thereafter. The key story related to this is of course what we know as the Maccabean Revolt. And here's basically what happened. The Seleucid King Antiochus the Fourth ... comes through Jerusalem, and because the Jewish people are in resistance to some of his oppressive policies he decides to make a show of his power, and to make an example of the Temple. As the story goes, he then marches into the Temple, desecrates the Temple, puts a pig on the altar of sacrifice and generally does everything you shouldn't do in the Temple of Jerusalem. This experience is really one that galvanizes most of the negative reaction that we hear in later Jewish tradition. It also galvanizes a political response. Shortly after his desecration of the Temple, a small band of warriors under Judas the Maccabee--his name literally means Judas the hammer--began a kind of guerrilla war against these Greek armies. And interestingly enough they managed to win a lot of battles, quite surprisingly from the size and strength of the Greek army. The culmination of this story is when in the year 164 a small band under command of Judas himself actually manages to retake the Temple and, while holding off the Greek armies, proceeds then to repurify and rededicate the Temple. That is the event celebrated as the feast of dedication, better known as Hanukkah. ... For the first time since the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem the

Jewish people are facing a power that, as it would seem, wants to

destroy them and their religious tradition. ... So the responses that we

get in the Maccabean Revolt are extremely influential later on. On the

one side we have the response of Judas and his followers. To fight, to

defend the land and its traditions. The theology of the Maccabean

revolutionaries is, "God helps those who help themselves." But the other

response equally caught up in these ideas of the tension between good

and evil and of preserving nationhood is the response that says we have

to remain faithful and God will deliver us. And that's the response that

we get in the

Book of Daniel which takes it even more into an apocalyptic vein.

This period of Roman expansion is one that will lead up to what we think of as the beginning of the Roman Empire. It starts with conquest, with the expansion of empire under these late republican generals like Julius Caesar and Pompeii. They acquire land, provinces. After the assassination of Julius Caesar, however, in the forties, there will be a new turn that is taken in Roman political history when Julius Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, assumes the title of Augustus and proclaims himself emperor of the Roman Empire. After his famous conflict with Anthony and Cleopatra, he will now not only control Rome but its vast empires all the way from Spain and Britain in the west to the Persian Gulf in the East, and the prize in part is Egypt itself. But one of the gateways to the East is the land of Judaea on the eastern Mediterranean shores, which becomes one of his points of entry into this political realm. So here, once again, is, and we see throughout this period of history, little Judaea is central to the story of politics and power throughout the Mediterranean world ... . Now because of the sense of building the empire and the glory that's

created under Augustus, the Romans start to have what we might call an

ideology of empires, sometimes referred to as the Pax Romana, the peace

of Rome. But there is a sense of what we might think of as manifest

destiny. ... It was the will of the gods that this should happen. It was

our role in history because of our virtue and our strength and our

nobility. ... Now we have to put this way of thinking along side of

Jewish sense of destiny, a destiny often reflected as a plan of God

worked out through a revealed sense of history, in apocalyptic

tradition. But now we're watching that

Jewish sense of destiny run into conflict with the Roman sense of

destiny. ...

So what did some of them do? Some people then left Jerusalem entirely. This is what the Essene [group] seems to have done. They moved off to the to the Dead Sea to form a pure priestly community until such time that the Messiahs would come, recapture the Temple and restore it to its purity. So they're really looking forward to a time when the forces of God will take Jerusalem once again.

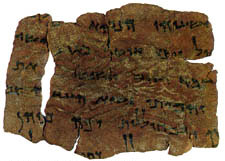

What were the Dead Sea Scrolls? The Dead Sea Scrolls, which were discovered in 1947 in caves along

the banks of the Dead Sea near where the Essene community was founded,

contained a number of different documents. Many thousands of fragments

have actually been discovered. But basically, [there are] three key

types ... . First, copies of all of the biblical texts from the Hebrew

scriptures, including text of

First Enoch and other apocalyptic literature of this period. In most

cases, these manuscripts are our oldest known copies of all the ancient

biblical literature. Secondly, it contains commentaries on these texts.

And a particular type of commentary, the Essene style of commentary

called [pesharim]. It's from the word which mean, "this is interpreted."

The pesher is a way of doing commentary where they take passages from

older scriptures and say how they are to be interpreted for the present

day. ... The third type of literature that we have among the Dead Sea

scrolls is what is usually referred to as their sectarian writings.

These are scrolls that refer to the community themselves and how they

live and how they think. One of these is called the

Rule of the Community and explains the very difficult procedure of

getting in and how you have to go through several stages of initiation

and rigorous kind of examination and it sounds somewhat like a monastic

community. Another document out of this group is what's called the

War Scroll. And it is quite literally their battle plan for the

battle at the end of the ages. It starts off this is the war of the sons

of light against the sons of darkness. And they think of it quite

literally as the way the final battle will be carried out.

Were John the Baptist and Jesus in the same traditions as the Essenes? The Essenes weren't the only such new voices of protest and

expectation at this time. We hear of quite a number of others ... some

of them calling for different kinds of religious reform and different

kinds of ways of looking at the hope of Israel. And two of the best

known figures of this period are

John the Baptist and Jesus, both of whom come out of this early very

Jewish apocalyptic tradition, both calling for an expectation of a new

kingdom. The classic formulation of John the Baptist is, "Repent, for

the kingdom of heaven is at hand. Let's return to a pure nation of

Israel." And in the case of Jesus it's also, "The kingdom is at hand."

But the classic statement of Jesus, more profound and in some ways more

problematic later on, is the one that looks down the road for the

kingdom to come. In several passages we hear it something like this.

"For some of you standing here," and he's talking to his own group of

disciples around him ... "will not taste death until you see the kingdom

come with power." But they expect something to happen soon. Even a full

generation after the death of Jesus ... they still think that the second

coming of Jesus and the arrival of the kingdom would be something that's

just around the corner ... .

Diverse as their religious outlooks may have been, these different

streams of apocalyptic expectation all came together in about the year

66 when there was an outbreak of war against the Romans. This war would

last for four years, and it would result in a devastating destruction of

Jerusalem once again. But it [had] more clearly been fought as a war

against Roman oppression, where the Romans are viewed as the evil

empire, the forces of Satan, and the Jewish armies then see themselves

as the forces of God trying to expel them ... . The Jewish War began ...

with a great deal of hope and expectation. This was to be the messianic

war. This was to be the triumph of Israel. The war ended on a very

different note. After successive losses and some devastating battles

with massive loss of life, eventually the Roman armies bottled up the

remaining revolutionaries in the city of Jerusalem itself. Then there

was a long and

protracted siege which had the result of greater loss of life and

starvation and horrendous stories of death. And in the end a final siege

where the Romans broke through the city walls, burned and destroyed the

city and worst of all destroyed the Temple itself once again. So from

the perspective of the Jewish mind, and for very many people in this

period, the hope of triumph and victory is has now been dashed with the

very thing they thought could never happen again. Namely the Temple

destroyed. And the trauma of that experience, then the trauma of

rethinking what it means for our understanding of what God has in store

for us had to be tremendous. For some it was another moment where they

had to say, "We've done something wrong, we must have sinned ... . " For

others maybe it's only the beginning of a new stage of history where the

final victory is just about to come. The destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E. leads to yet another

stage of apocalyptic reinterpretation. They have to retell their story.

They have to rethink their own past. ... In the period between roughly

75 and 100 CE we have a proliferation of new Jewish apocalypses,

documents like Fourth Israel, or Second Baruch, or the Apocalypse of

Abraham. All figures from ancient Jewish history now are the sources for

a new understanding of the future. In a similar way the

early Christians, who at this point in time are largely still within

the larger framework or Judaism, also have to reinterpret their

understanding of history. Some of their expectations for the war did not

come to pass. Many of them apparently thought that this was going to be

the return of Jesus, and that Jesus was at this time going to restore

the kingdom to Israel. So it is in the period, between roughly 70 and

100, on the Christian side that we find a new conceptualization of

apocalyptic tradition, a new sense of what will be God's plan for the

future, and for the eschaton. Among the writings that we have in this

period are the gospels. And in all of the gospels of this generation, we

hear of attempts to explain what Jesus really intended for the eschaton,

and what was misunderstood by people of an earlier generation. We get

new writings attributed to Paul or Peter to explain eschatology. Some of

these also are in the New Testament. And then we get the

Book of Revelation. ... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||