from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/elegant/everything.html

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

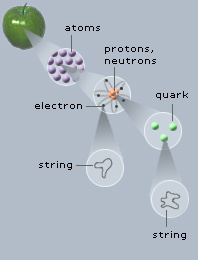

Note: For a definition of unfamiliar terms, see our glossary. The fundamental particles of the universe that physicists have identified—electrons, neutrinos, quarks, and so on—are the "letters" of all matter. Just like their linguistic counterparts, they appear to have no further internal substructure. String theory proclaims otherwise. According to string theory, if we could examine these particles with even greater precision—a precision many orders of magnitude beyond our present technological capacity—we would find that each is not pointlike but instead consists of a tiny, one-dimensional loop. Like an infinitely thin rubber band, each particle contains a vibrating, oscillating, dancing filament that physicists have named a string. In the figure at right, we illustrate this essential idea of string theory by starting with an ordinary piece of matter, an apple, and repeatedly magnifying its structure to reveal its ingredients on ever smaller scales. String theory adds the new microscopic layer of a vibrating loop to the previously known progression from atoms through protons, neutrons, electrons, and quarks. Although it is by no means obvious, this simple replacement of point-particle material constituents with strings resolves the incompatibility between quantum mechanics and general relativity (which, as currently formulated, cannot both be right). String theory thereby unravels the central Gordian knot of contemporary theoretical physics. This is a tremendous achievement, but it is only part of the reason string theory has generated such excitement.

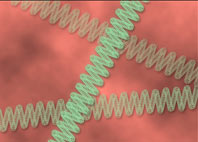

In Einstein's day, the strong and weak forces had not yet been discovered, but he found the existence of even two distinct forces—gravity and electromagnetism—deeply troubling. Einstein did not accept that nature is founded on such an extravagant design. This launched his 30-year voyage in search of the so-called unified field theory that he hoped would show that these two forces are really manifestations of one grand underlying principle. This quixotic quest isolated Einstein from the mainstream of physics, which, understandably, was far more excited about delving into the newly emerging framework of quantum mechanics. He wrote to a friend in the early 1940s, "I have become a lonely old chap who is mainly known because he doesn't wear socks and who is exhibited as a curiosity on special occasions." Einstein was simply ahead of his time. More than half a century later, his dream of a unified theory has become the Holy Grail of modern physics. And a sizeable part of the physics and mathematics community is becoming increasingly convinced that string theory may provide the answer. From one principle—that everything at its most microscopic level consists of combinations of vibrating strands—string theory provides a single explanatory framework capable of encompassing all forces and all matter. String theory proclaims, for instance, that the observed particle properties—that is, the different masses and other properties of both the fundamental particles and the force particles associated with the four forces of nature (the strong and weak nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity)—are a reflection of the various ways in which a string can vibrate. Just as the strings on a violin or on a piano have resonant frequencies at which they prefer to vibrate—patterns that our ears sense as various musical notes and their higher harmonics—the same holds true for the loops of string theory. But rather than producing musical notes, each of the preferred mass and force charges are determined by the string's oscillatory pattern. The electron is a string vibrating one way, the up-quark is a string vibrating another way, and so on. Far from being a collection of chaotic experimental facts, particle properties in string theory are the manifestation of one and the same physical feature: the resonant patterns of vibration—the music, so to speak—of fundamental loops of string. The same idea applies to the forces of nature as well. Force particles are also associated with particular patterns of string vibration and hence everything, all matter and all forces, is unified under the same rubric of microscopic string oscillations—the "notes" that strings can play.

For the first time in the history of physics we therefore have a framework with the capacity to explain every fundamental feature upon which the universe is constructed. For this reason string theory is sometimes described as possibly being the "theory of everything" (T.O.E.) or the "ultimate" or "final" theory. These grandiose descriptive terms are meant to signify the deepest possible theory of physics—a theory that underlies all others, one that does not require or even allow for a deeper explanatory base. In practice, many string theorists take a more down-to-earth approach and think of a T.O.E. in the more limited sense of a theory that can explain the properties of the fundamental particles and the properties of the forces by which they interact and influence one another. A staunch reductionist would claim that this is no limitation at all, and that in principle absolutely everything, from the big bang to daydreams, can be described in terms of underlying microscopic physical processes involving the fundamental constituents of matter. If you understand everything about the ingredients, the reductionist argues, you understand everything. The reductionist philosophy easily ignites heated debate. Many find it fatuous and downright repugnant to claim that the wonders of life and the universe are mere reflections of microscopic particles engaged in a pointless dance fully choreographed by the laws of physics. Is it really the case that feelings of joy, sorrow, or boredom are nothing but chemical reactions in the brain—reactions between molecules and atoms that, even more microscopically, are reactions between some of the fundamental particles, which are really just vibrating strings? In response to this line of criticism, Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg cautions in Dreams of a Final Theory: At the other end of the spectrum are the opponents of reductionism who are appalled by what they feel to be the bleakness of modern science. To whatever extent they and their world can be reduced to a matter of particles or fields and their interactions, they feel diminished by that knowledge....I would not try to answer these critics with a pep talk about the beauties of modern science. The reductionist worldview is chilling and impersonal. It has to be accepted as it is, not because we like it, but because that is the way the world works. Some agree with this stark view, some don't. Others have tried to argue that developments such as chaos theory tell us that new kinds of laws come into play when the level of complexity of a system increases. Understanding the behavior of an electron or quark is one thing; using this knowledge to understand the behavior of a tornado is quite another. On this point, most agree. But opinions diverge on whether the diverse and often unexpected phenomena that can occur in systems more complex than individual particles truly represent new physical principles at work, or whether the principles involved are derivative, relying, albeit in a terribly complicated way, on the physical principles governing the enormously large number of elementary constituents. My own feeling is that they do not represent new and independent laws of physics. Although it would be hard to explain the properties of a tornado in terms of the physics of electrons and quarks, I see this as a matter of calculational impasse, not an indicator of the need for new physical laws. But again, there are some who disagree with this view.

What is largely beyond question, and is of primary importance to the journey described in my book The Elegant Universe, is that even if one accepts the debatable reasoning of the staunch reductionist, principle is one thing and practice quite another. Almost everyone agrees that finding the T.O.E. would in no way mean that psychology, biology, geology, chemistry, or even physics had been solved or in some sense subsumed. The universe is such a wonderfully rich and complex place that the discovery of the final theory, in the sense we are describing here, would not spell the end of science. Quite the contrary: The discovery of the T.O.E.—the ultimate

explanation of the universe at its most microscopic level, a theory that

does not rely on any deeper explanation—would provide the firmest

foundation on which to build our understanding of the world. Its

discovery would mark a beginning, not an end. The ultimate theory would

provide an unshakable pillar of coherence forever assuring us that the

universe is a comprehensible place.

|

|

||||||||||

|